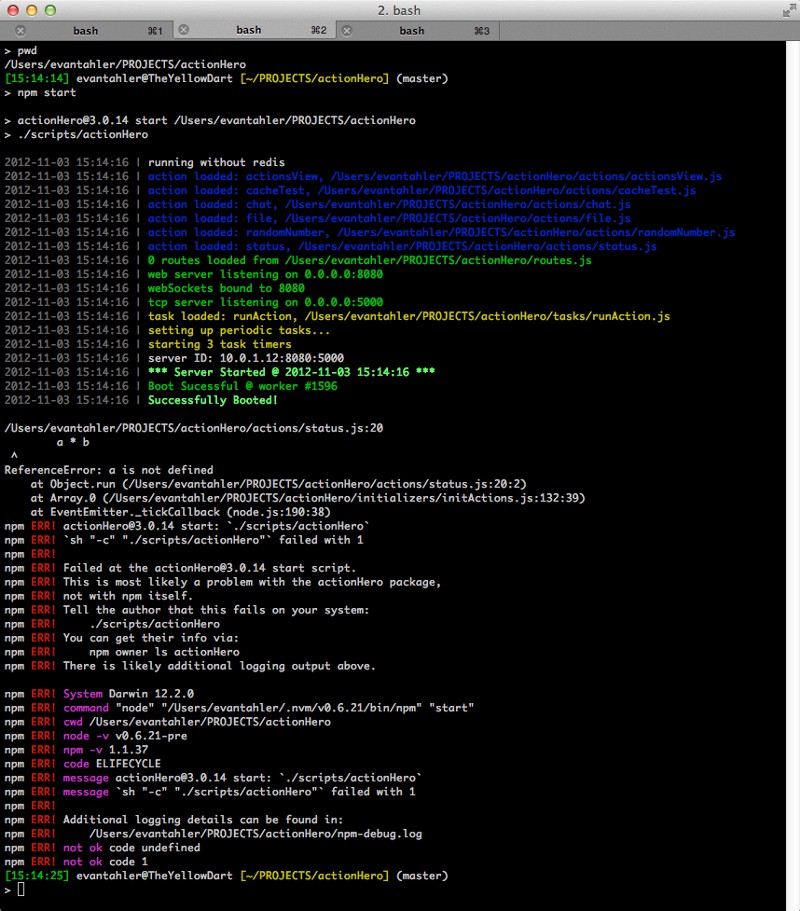

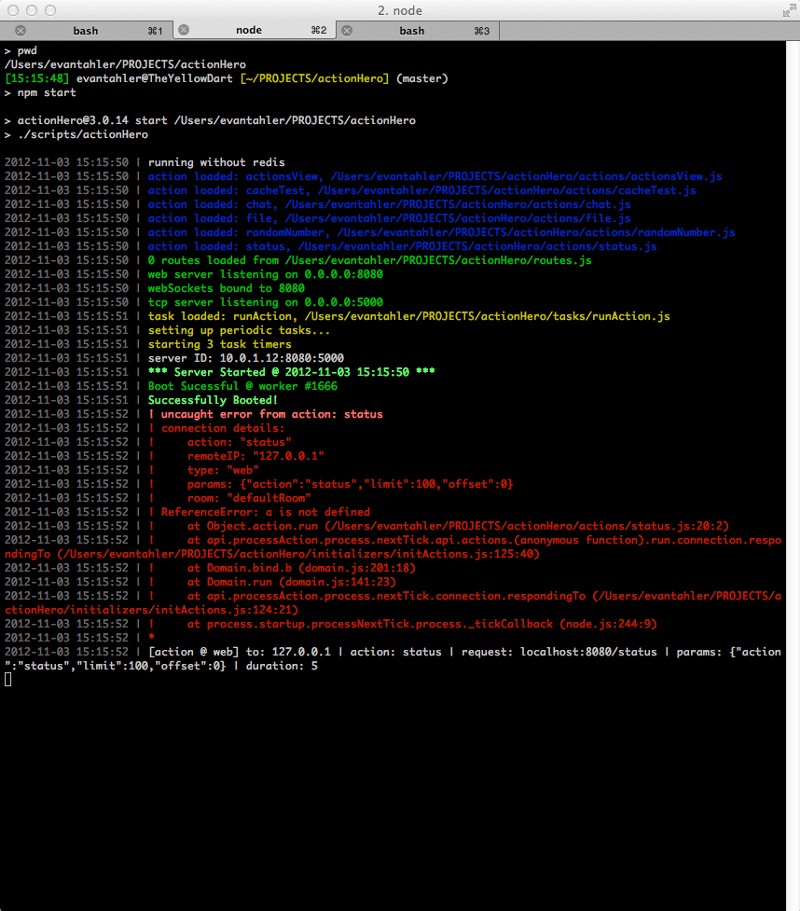

Recently we added support for a ‘developer mode’ to ActionHero which reloads parts of your project on the fly as you develop. Doing so enabled developers to go from seeing A to B

A: Wild Exceptions

B: Caught Exceptions

Notice that not only did the application not crash in a fiery blaze, but it also returned a meaningful response back to the user ({ "error":"The server experienced an internal error" } along with a classy ‘500’ header ) . When using developer mode, ActionHero watches various files for changes, and reloads them on the fly. However, if you are like me, you are very likely to introduce a bug as you are developing. In the above example, I referenced a variable that wasn’t defined, but it’s just as likely that I might have broken the parser with some malformed JSON. When fleshing out the ‘safety features’ around developer mode (which makes liberal use of domains), I realized that there are actually 4 classes of exceptions in node, and they each have their own patterns of error handling:

- Synchronous Exceptions

- Asynchronous Exceptions

- callback(error, data)

- callback(modifiedObject, nextAction)

- Domain Exceptions

Footnote: We are talking about Exceptions not Strings

First, let’s clear up that we are talking about exceptions and not passing strings or null around. Other folks have written eloquently on the topic, so let me just say that in node, there is a difference between ‘throw "my error";’ and ‘throw new Error("my error");’ most important of which is the stack trace. The node Error object has all sorts of great properties which you should check out in the docs.

Synchronous Exceptions

For synchronous functions, the most common pattern when something goes wrong is to throw an Error object. Generally speaking, returning both ‘null’ and ‘false’ might have syntactic meaning (AKA: I have null results to return), so they might be misinterpreted by clients. This might seem like it is breaking the ‘promise’ set up by using a function (in that it should return a value in all cases), but choosing to thow an exception is a blocking way to denote that a blocking function has something wrong with it

Here’s a simple example:

1var addSync = function (a, b) { 2 if (!isNumber(a)) { 3 throw new Error(a + " is not a number"); 4 } 5 if (!isNumber(b)) { 6 throw new Error(b + " is not a number"); 7 } 8 return parseFloat(a) + parseFloat(b); 9}; 10 11function isNumber(n) { 12 return !isNaN(parseFloat(n)) && isFinite(n); 13}

When using this pattern, the callers of your method can be sure that the function worked as intended, or that an error was thrown. Now, you might not want that thrown exception to crash you application so you can use JS’ try/catch functions to wrap a function which you think might thrown an exception. In this manner you can also chose to do whatever you want with the exception object returned, including displaying its stack trace, etc. This programming style enforces that your methods are called ‘correctly’ (as you have defined ‘correct’ to be), and developers must opt-in to treating your metod in a ‘fuzzy’ way by wrapping it with a try/catch block. By the way, javascript’s try{} catch(e) {} methods only work with synchronous functions.

1try{ 2 addSync(1, "word"); 3 console.log("YAY"); 4}catch(err){ 5 console.log(err.stack); 6} 7 8Error: word is not a number 9 at addSync (/Users/evantahler/Desktop/test.js:3:28) 10 at Object. (/Users/evantahler/Desktop/test.js:11:14)

Sometimes you don’t have the ability to ensure that your functions return an error rather than throw it. For example, the ‘require’ method will throw an error if the file you are loading has a syntax error. In these situations you have 2 options: either wrap the call in a try/catch, or use node’s ‘process.on(‘uncaughtException’, function(err) { })’ global catch.

It’s generally a bad idea to use this global catcher as you might be ignoring important errors which really should cause your application to stop. In actionHero, loading in all user-created files (actions, tasks, routes, etc) are wrapped in a try/catch block so that one bad action won’t stop your application from booting (but we will log a nice error message for you), while loading the core actionHero files should still cause the application to crash if something is wrong with them.

Asynchronous Exceptions

There are 2 common async patterns in node: the callback(error, data) pattern and the callback(modifiedObject, nextAction) pattern.

The most common pattern for async code is to respond to the callback with callback(error, data). This pattern follows a similar ‘promise’ an async function makes, mainly that it will eventually respond to it’s callback with information on its own operation (error) and any results of the operation. What’s nice about the (err, data) pattern is that you can always expect 2 values, and you can’t confuse which is which.

1var addAsync = function (a, b, next) { 2 if (typeof next != "function") { 3 return new Error("this is an async function and expects a callback"); 4 } 5 if (!isNumber(a)) { 6 next(new Error(a + " is not a number"), null); 7 } else if (!isNumber(b)) { 8 next(new Error(b + " is not a number"), null); 9 } else { 10 next(null, parseFloat(a) + parseFloat(b)); 11 } 12}; 13 14function isNumber(n) { 15 return !isNaN(parseFloat(n)) && isFinite(n); 16}

Happily in javascript, ‘null == true’ responds with false, so you can check the results of any asynchronous function using this pattern with ‘if(err){ } else { }’.

In ActionHero, every action and task is technically one big async function and we use the second callback pattern. First, we know that the callback for every action will always be to some sort of renderer (depending on the connection type), and we know that we always must must respond to the client, even if there is an error. With this knowledge, we can enforce the rule that all action’s callbacks are next(connection, toRender). toRender in this case is a boolean instructing the callback weather or not it needs to render a response to the client. For example, if the action was "file", and the action already streamed down the contents of a .jpg, there’s nothing left to send to the client. But what about errors?

In actions, we are always passing around the ‘connection’ object, and this object’s connection.error state is very important. It’s not only rendered back to the user, but it can also be used as a mechanism for flow control. actionHero’s promise pattern is modified to use a data object (in this case, connection) to reflect state. For example, if String(connection.error) == "user not authenticated" rather than null, you know that you probably shouldn’t run that ‘changePassword()’ method next. The promise here now becomes that the async function will always return a modified version of the data object passed to it , and instructions on what to do next.

An example of actionHero’s type of callback pattern is:

1var addAsyncWithDataObject = function(object,next){ 2 if(!isNumber(object.a)){ object.error = new Error(object.a + ' is not a number'); } 3 else if(!isNumber(object.b)){ object.error = new Error(object.b + ' is not a number'); } 4 else{ object.result = parseFloat(a) + parseFloat(b); } 5if(object.error == null{ 6 next(object, true); 7 }else{ 8 next(object, false); 9 } 10 } 11 12 function isNumber(n) { 13 return !isNaN(parseFloat(n)) && isFinite(n); 14 }

This version of the async function would be called like this:

1data = { 2 a: 1, 3 b: 2, 4}; 5addAsyncWithDataObject(data, function (data, toRender) { 6 if (!toRender) { 7 // handle error 8 } else { 9 // yay 10 } 11});

Domain Exceptions

In recent node.js versions ( version >= 0.8.0 ), domains have been introduced. Domains are a tool with which you can wrap a section of your code in an asynchronous container. Think of them like a async version of try / catch. An example:

1var domain = require(‘domain’); 2 3var addAsync = function(a,b,callback){ 4 if(!isNumber(a)) { throw new Error(a + “is not a number”); } 5 if(!isNumber(b)) { throw new Error(b + “is not a number”); } 6 var response = a + b; 7 callback(null, response); 8} 9var isNumber = function(n) { 10 return !isNaN(parseFloat(n)) && isFinite(n); 11 } 12 13 var containWithDomain = function(a,b,callback){ 14 var wrapper = domain.create(); 15 wrapper.on(“error”, function(err){ 16 callback(new Error(“caught by domain”), null); 17 }); 18 wrapper.run(function(){ 19 var response = add(a,b, function(err, response){ 20 callback(err, response); 21 }); 22 }); 23 }

Here you can see that our addAsync method now throws errors rather than passing them to the callback. Left uncaught, they would normally crash the application. However, if we use containWithDomain() rather than addAsync(), we can actually catch those thrown errors and handle them in a meaningful way. Domains are great when you don’t know exactly what the underlying code is doing, but should be avoided in favor of one of the first 2 patterns whenever possible.

ActionHero users domains to run users’ action and task code within to ensure that one poor action won’t crash the whole app (and how we are able to catch exceptions and render custom error traces as shown in the image above). You can see actionHero’s exception code here.

Thanks!

I write about Technology, Software, and Startups. I use my Product Management, Software Engineering, and Leadership skills to build teams that create world-class digital products.

Get in touch